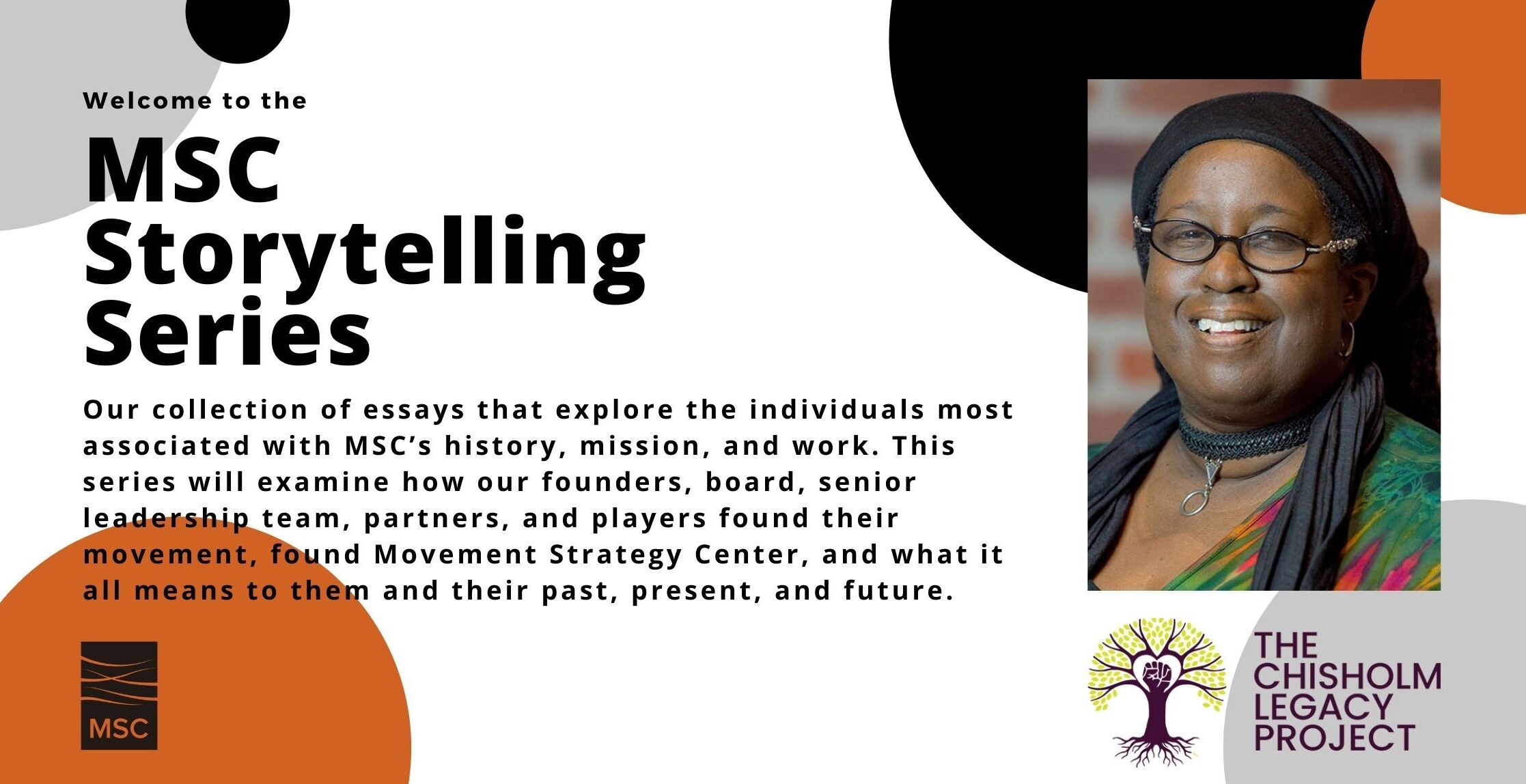

Our Storytelling Series Features the Folks Most Associated With MSC's History: Meet Jacqui Patterson

In this installment we get to know researcher, advocate, and activist Jacqueline “Jacqui” Patterson founder and executive director of the Chisholm Legacy Project — former director of the NAACP Environmental and Climate Justice Program; co-founder of Women of Color United; and proud board member of MSC.

“It wasn’t a coincidence, it wasn’t happenstance.” So says Jacqui Patterson — activist, founder of the Chisholm Legacy Project, and MSC board member — on how she made her way to Movement Strategy Center.

She was introduced to MSC through Movement Generation but if it wasn’t that it would’ve been something else: “the universe … draws like-mission and like-spirited people together.” She knew from the beginning there was alignment in work and in mission and it became clearer as Patterson participated in MSC’s movement support work — the Transitions Labs, the facilitation of conversations and meetings, and the cultivation of projects. “There are so many points of resonance and alignment in everything that MSC does … Whether it is the heart of the people … Or the way that they facilitate conversations about collective organizing toward the world that we want, MSC has been an inspiration, a catalyst, and a facilitator of radical imagination and a radical love in action.”

Patterson hails from the southside of Chicago — a very urban place not far from the other, more suburban side of the tracks. Her neighborhood offered many of the great touchstones of city life — ice cream trucks, block parties, and community. But also some of the worst: there were gangs, the sound of gunshots weren’t uncommon, and concerns about her brother simply existing as a Black boy in America were pervasive.

Her family blended two cultures — her mother came up to Chicago during the Great Migration from Dublin, Mississippi; her dad immigrated there from Jamaica. The result was an upbringing steeped in both Deep South and Jamaican influences: a culture of food (collard greens plus curried chicken) and music (rhythm and blues plus reggae). Patterson’s ancestry is in sub-Saharan Africa; her common history involves those ancestors being stolen from their homelands and brought to unceded territories in both the United States and Jamaica to become the enslaved labor behind the economy and the infrastructure of those respective lands.

She says, “I am who I am out of that history and that story. And, I am who I am in celebration of the rich cultural heritage and in resistance to and in reparations from how the heritage and ties to nation and community were interrupted by colonialism. I do what I do to both celebrate and treasure that cultural heritage.”

There are so many points of resonance and alignment in everything that MSC does … Whether it is the heart of the people … Or the way that they facilitate conversations about collective organizing toward the world that we want, MSC has been an inspiration, a catalyst, and a facilitator of radical imagination and a radical love in action.

Her work reflects this. She is working to restore “linkages in some ways to the motherland,” and “address, redress, and correct the carnage and the aftermath of colonialism and where it has left our communities as a result of the systemic exploitation, extraction, and oppression.” The work centers on Black and BIPOC communities all over the world; and is in partnership with all “the aligned and the allied — anyone who is allied and aligned with the mission of Black liberation.”

For her, liberation ensures “that all people have self determination and have what they need to be whole and thriving.” And it starts with accountability — “my purpose is to be in service to the quest for self determination and liberation of Black frontline communities.”

So much of that begins with being very “intentional about who is not even being thought of by those sitting at the table — much less are they even at the table.” In terms of climate justice, Patterson wants everyone to have a seat. Thus, a focus on chronically ignored Freedman’s Settlements — communities, many unincorporated, established by those “just emancipated from enslavement.”

One, a community of only about 100 people outside Dallas, is Sandbranch, Texas. Stunningly, this unincorporated village adjacent to one of our country’s wealthiest cities has never had running water. Their well water was contaminated in the 1980s, and today, residents rely mainly on donated bottled water — not just for drinking, but for cooking and bathing. Stories like these are at the center of the Patterson-founded Chisholm Legacy Project — an organization that connects Black communities on the frontlines with the resources necessary to implement transformation.

It isn’t easy work. And that’s why Patterson so valued the aforementioned Transitions Labs — these safe spaces offered community and reflection. A way to, at least metaphorically, refill your cup. These gatherings also made it clear that “all the work around social justice and systems change is intersectional.” A priceless opportunity “to explicitly be engaged with folks who are doing work from gender justice to education justice to general economic justice and so forth, and to really come together and talk about this notion of Just Transition and this ideal that we want as a society.” She acknowledges the concept “might sound utopian,” but for the frontliners in attendance that discussion and that space is “a necessity in order to survive and thrive as people.”

All the work around social justice and systems change is intersectional.

It can be hard for outsiders to understand what these retreats and workshops were like. Patterson describes them as a chance to step “away from the day to day, the list of deliverables … The nonprofit industrial complex.” Crucially, they offered an opportunity to discuss the roles and purpose of both the individuals and the organizations across various movements in “a space of ideating … Set up to accommodate all learning and being styles.”

Attendees showed up with “a selfless sense of mission, so there was a level of trust and safety there.” And the work — deep conversation and reflection, “the practices: tai chi, somatics, embodiment … Various exercises that got you out of your head and into the culture” — fostered intimate connection. “We can go whole days, weeks, or months without thinking about that larger arc,” so the safe space to simply “think and be” was invaluable and unlike so many other gatherings and workshops.

It was at one of these Transitions Labs in the Redwood Forest — “a generative environment” — that Patterson felt everything sort of gel: her work, her goals, her collaborations with MSC. The activity at hand involved focusing on “developing a seed of an idea and being with people who were like-minded, like-focused, and like-spirited who were also growing their own seeds.” The seed that “began to truly blossom” for Patterson that day — while laying on the floor with her peers and remembering the iconic book the Bridge Called My Back, a collection of radical writings by Black women — involved “work specifically focused on supporting the wellbeing of Black femmes.”

That “unformed dream” turned “into an action plan … That birthed the fourth element of focus of the Chisholm Legacy Project — the focus on Black femme support.” Patterson explained that she had observed the “level of weight on Black femmes in terms of holding so much, our families, our organizations, the movement, in the case of Alabama and Georgia — actual democracy. Yet so often you see our sisters in the struggle are so weighed down by that.”

Sighting stress, premature deaths, and all the ways these weights can negatively manifest in the health of her peers inspired the project’s steadfast support of wellbeing. She believes this concept of “community care, organizational care, movement care — instead of just preaching self care to someone who is always going to put themselves last” is crucial to the future of the movement.

Today, Patterson feels honored to continue to support MSC as a board member, calling the work “a blessing.” Likewise, she values “the opportunity to continue to be in relationship with the innovations team that is doing amazing work,” citing her participation as a founding member of the National Association of Climate Resilience Planners. She looks forward to “continuing to support Climate Innovation’s (soon to be renamed People’s Climate Innovation Center (PCIC)) team” and ensuring “that the communities that we work with — including the Black femme climate justice leaders — are able to connect with and be nurtured by the rich range of offerings that MSC has,” especially in terms of climate resilience planning and training and Black youth leadership development.

And, circling back to the Freedman’s Settlements and towns like Sandbranch, she looks forward to growing “the ways that MSC’s fiscal sponsorship and regranting programs can benefit some of the most marginalized Black communities in the United States.” She continued, “the hope is that MSC and the Chisholm Legacy Project can together support the self determination and liberation of these communities all over the nation.”

She also hopes that others — new friends of MSC, new members of the collective movement ecosystem — get the chance to experience something like MSC’s Transitions Labs. They so deeply and positively affected Patterson and she recalled — with a lot of laughter and a little bit of embarrassment — one opportunity where participants were invited to write letters of appreciation to each other. “Other people maybe wrote one or two and I literally sat there and wrote super sappy love letters to everyone. I was just feeling literally just full of so much love for everyone who participated.”