Reimagining History and Healing

April 8, 2024

MSC Celebrates Anasa Trouman’s Vision for Memphis as a Beacon of HopeAs Women’s History Month draws to a close and we approach the anniversary of the pivotal end of the sanitation workers’ strike on April 16, we seek to honor new chapters written in the legacy of this historical event by MSC’s board member Anasa Troutman and her work at Historic…

MSC Launches a Donor Advised Fund Program

March 12, 2024

New Program Gives Donors a Chance to be a Part of Their Own Impact Investing StoryIn late 2023, MSC launched the Movement Strategy Center Donor Advised Fund (DAF) program, allowing individuals, families, companies, private foundations, trusts, and other entities to invest their assets toward building community wealth and power for leaders on the frontlines of…

Language Matters: MSC Unveils Updated Glossary and Terms

February 6, 2024

A Collaborative Refresh Informed by Community Feedback — Explore the GuideAt Movement Strategy Center, our dedication to language as a transformative tool recently inspired a significant update to our Glossary and Terms to Avoid webpage — an in depth resource for definitions and terms to avoid within the Transformative Movement Building space. This inspiration…

Addressing and Accepting Conflict for Stronger Movements

February 6, 2024

MSC on Essential Mindset Shifts for Stronger MovementsWhat do you think of when you hear the word conflict? Maybe it’s that tense moment in a scary movie — spooky music and squeaking doors. Maybe it’s on the news — clashing heads of state and political unrest. Or, maybe it’s the shocking twist in that prestige drama you’re watching. Conflict is everywhere —…

Announcing Our Website’s New Landing Page: Why MSC?

January 10, 2024

Over a Year in the Making, Our New Landing Page is Also Our New DEI PageBack in 2022, Carla Dartis, MSC’s Executive Director, asked us to consider adding a DEI page to MSC’s website. Honestly, we — MSC’s small Communications Team — were taken aback by the request. DEI, or Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, “encompasses the symbiotic relationship, philosophy and…

BBQs, Barbers, & Beyond: After Incarceration’s Impact in Albany

October 29, 2023

Charting the Journey from Personal Transformation to Community SolidarityNavigating the path back into society after incarceration is a daunting task, made more challenging when coupled with the hardships of homelessness. Both reentry and homelessness, although different experiences, can lead to feelings of being undervalued or overlooked. This shared struggle…

Building Power Through Connection

October 28, 2023

A Convergence of Community, Collaboration, and Commitment Towards a Sustainable Future with When Black + Brown Go Green (WBBGG)Since its inception in 2018 in the San Gabriel Valley and Los Angeles, CA, where access to green spaces is not a given, When Black + Brown Go Green (WBBGG) has emerged as an intergenerational beacon for climate action and regenerative…

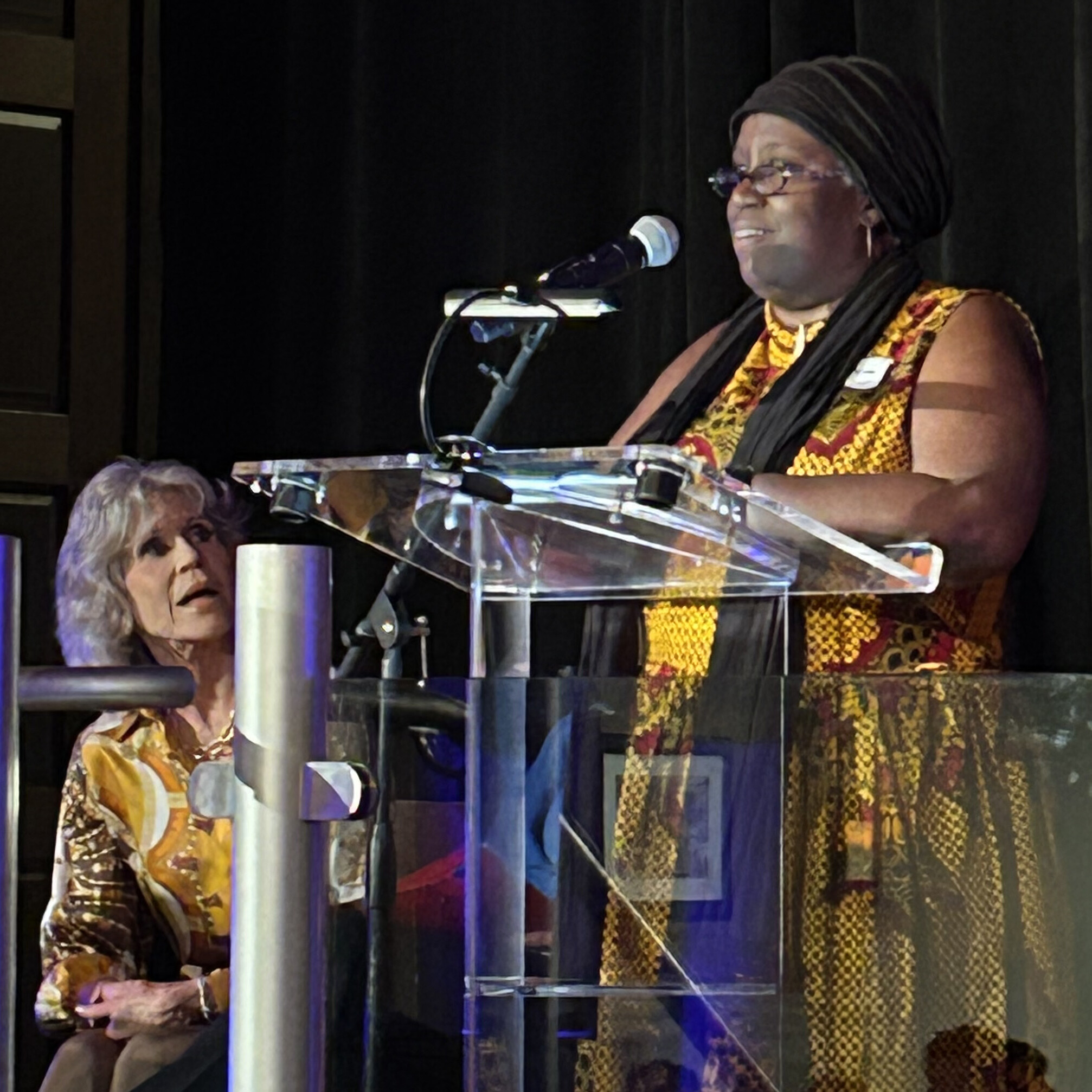

Gender Just Climate Solutions with Jane Fonda and Jacqui Patterson

September 25, 2023

A Climate Week Gathering Highlights Small Projects, Big Impacts, and the Work of WomenClimate Week NYC — the largest annual climate event of its kind — offers in-person, hybrid, and online events and activities for activists, businesses, and politicians from all over the world. Hosted by Climate Group, an international nonprofit that supports climate action, the…

Shaping the Future of Environmental Justice: A Conversation with MSC’s Environmental Fellow

September 7, 2023

Movement Strategy Center Explores Architecture, Community Engagement, and Mentorship with Walter HuntAt the core of the environmental movement is a vision to reshape and align our communities toward a regenerative relationship with the earth. At Movement Strategy Center (MSC), we’re not just embracing this vision; we’re cultivating the leaders who…

Growing Hope: Cultivating a Resilient Future in

Sandbranch, Texas

August 3, 2023

Movement Strategy Center Shares the Sandbranch Revitalization Fund’s ProgressSandbranch’s relationship with water paints a poignant narrative of resilience. The absence of safe, clean water reverberates throughout the entire fabric of the community, touching upon every aspect of life — people, productivity, and the natural world alike. Yet, amid these…