Addressing and Accepting Conflict for Stronger Movements

February 6, 2024

MSC on Essential Mindset Shifts for Stronger MovementsWhat do you think of when you hear the word conflict? Maybe it’s that tense moment in a scary movie — spooky music and squeaking doors. Maybe it’s on the news — clashing heads of state and political unrest. Or, maybe it’s the shocking twist in that prestige drama you’re watching. Conflict is everywhere —…

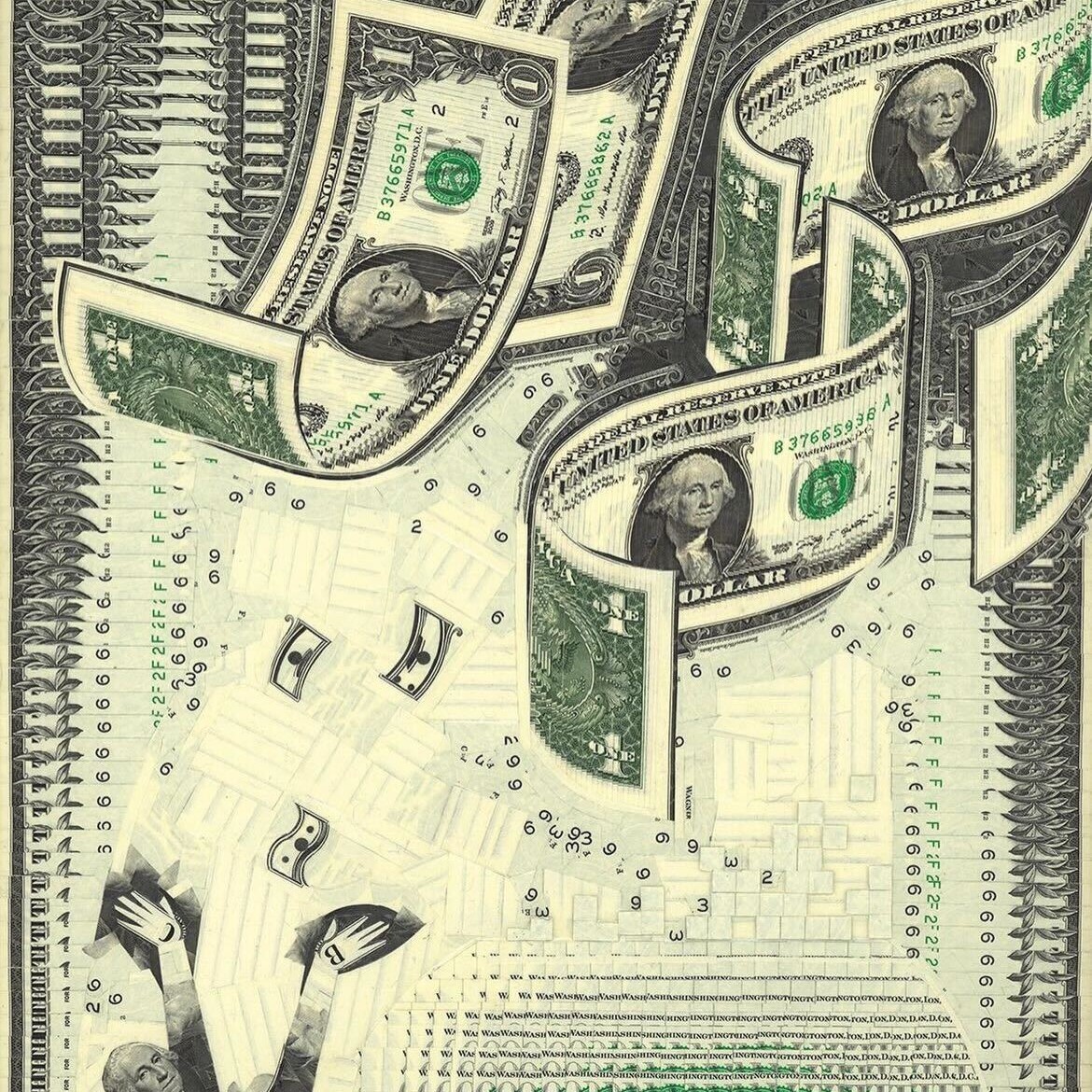

Moving Money Where it Matters

June 6, 2023

Movement Strategy Center on Shifting Philanthropic Power Dynamics Towards Interdependence and ResilienceEvery degree of warming intensifies the risk of species extinction, highlighting the urgency of addressing climate change. As we watch the weather report on any given day, the unfolding realities of our changing climate become strikingly evident — the record…

Navigating Tensions Within Capitalist Systems

April 11, 2022

Movement Strategy Center on Forging Authentic Relationships Between Funders and Movement LeadersMovement Strategy Center (MSC) is values-aligned with the activist organizations we offer infrastructure to and thought partnership with; and dismantling white supremacy in philanthropy and intermediary services is fundamental to our goal and mission. But at the end…

Essential Shifts in Funding Practices

September 7, 2021

Movement Strategy Center on How Philanthropy Must EvolveFunding Practices Today Last summer, we witnessed many institutions and nonprofits denounce systemic racism amid the world’s sharp focus on George Floyd’s murder and the larger Black liberation movement, yet few organizations have moved toward tangible action. A recent report from PolicyLink and Bridgespan…

Reconsidering Regranting

August 4, 2021

Movement Strategy Center Reimagines Equitable Regranting Through Philanthropic InnovationRegranting Today In 2006, Warren Buffett announced he would donate 85 percent of his Berkshire Hathaway stock to charity. At the time, Buffett was the richest person in the United States, and his portfolio of stock in the holding company he founded was worth $44 billion. But…