Building Power Through Connection

October 28, 2023

A Convergence of Community, Collaboration, and Commitment Towards a Sustainable Future with When Black + Brown Go Green (WBBGG)Since its inception in 2018 in the San Gabriel Valley and Los Angeles, CA, where access to green spaces is not a given, When Black + Brown Go Green (WBBGG) has emerged as an intergenerational beacon for climate action and regenerative…

HCC’s Decade ofCultivating Healing

October 11, 2023

Movement Strategy Center Celebrates Ten Years of Healing Clinic CollectiveCelebrating a decade of unwavering commitment to community health and healing, the Healing Clinic Collective (HCC) marks its tenth anniversary with a sense of accomplishment and purpose. Since its inception, HCC has been a beacon of hope and support for communities, offering accessible…

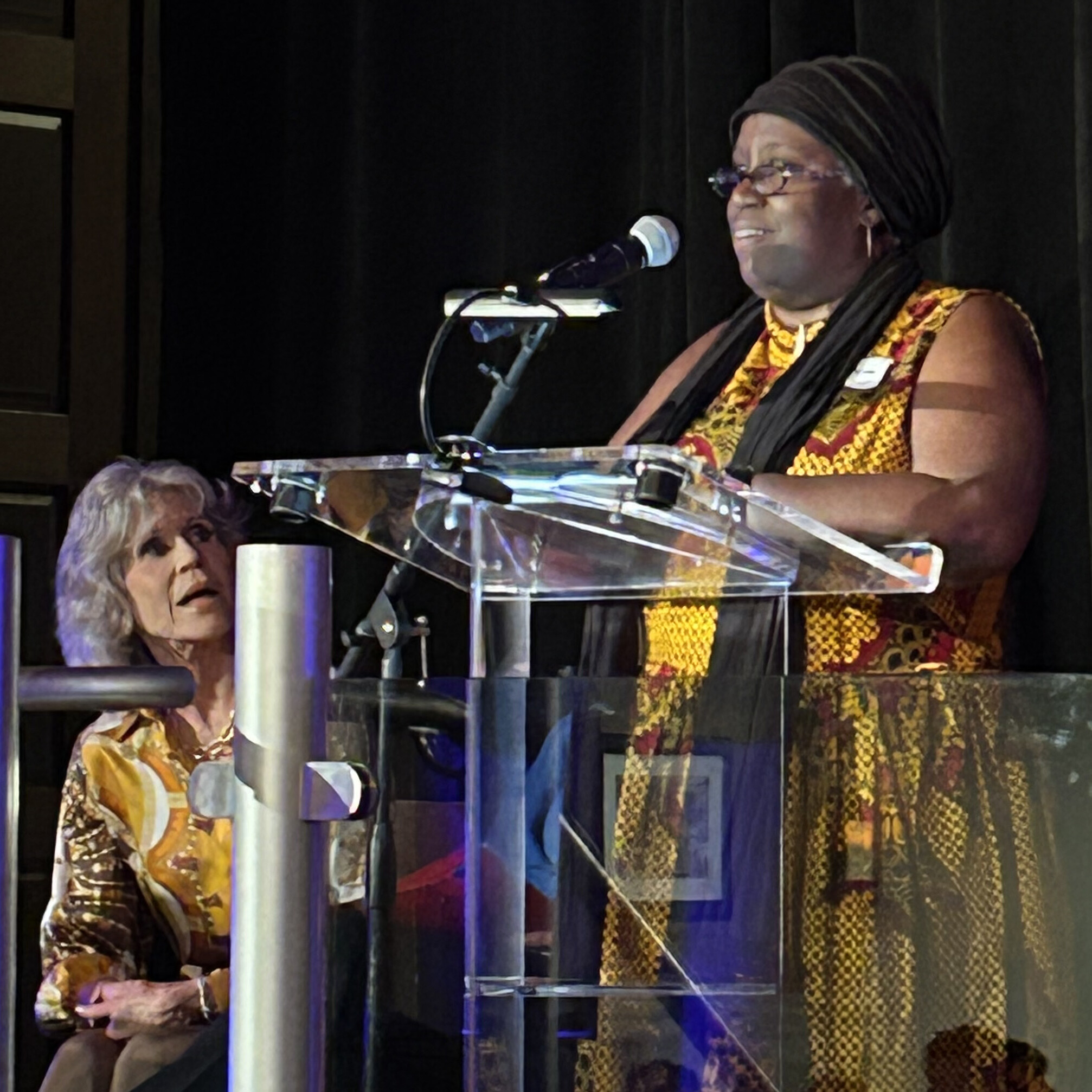

Gender Just Climate Solutions with Jane Fonda and Jacqui Patterson

September 25, 2023

A Climate Week Gathering Highlights Small Projects, Big Impacts, and the Work of WomenClimate Week NYC — the largest annual climate event of its kind — offers in-person, hybrid, and online events and activities for activists, businesses, and politicians from all over the world. Hosted by Climate Group, an international nonprofit that supports climate action, the…

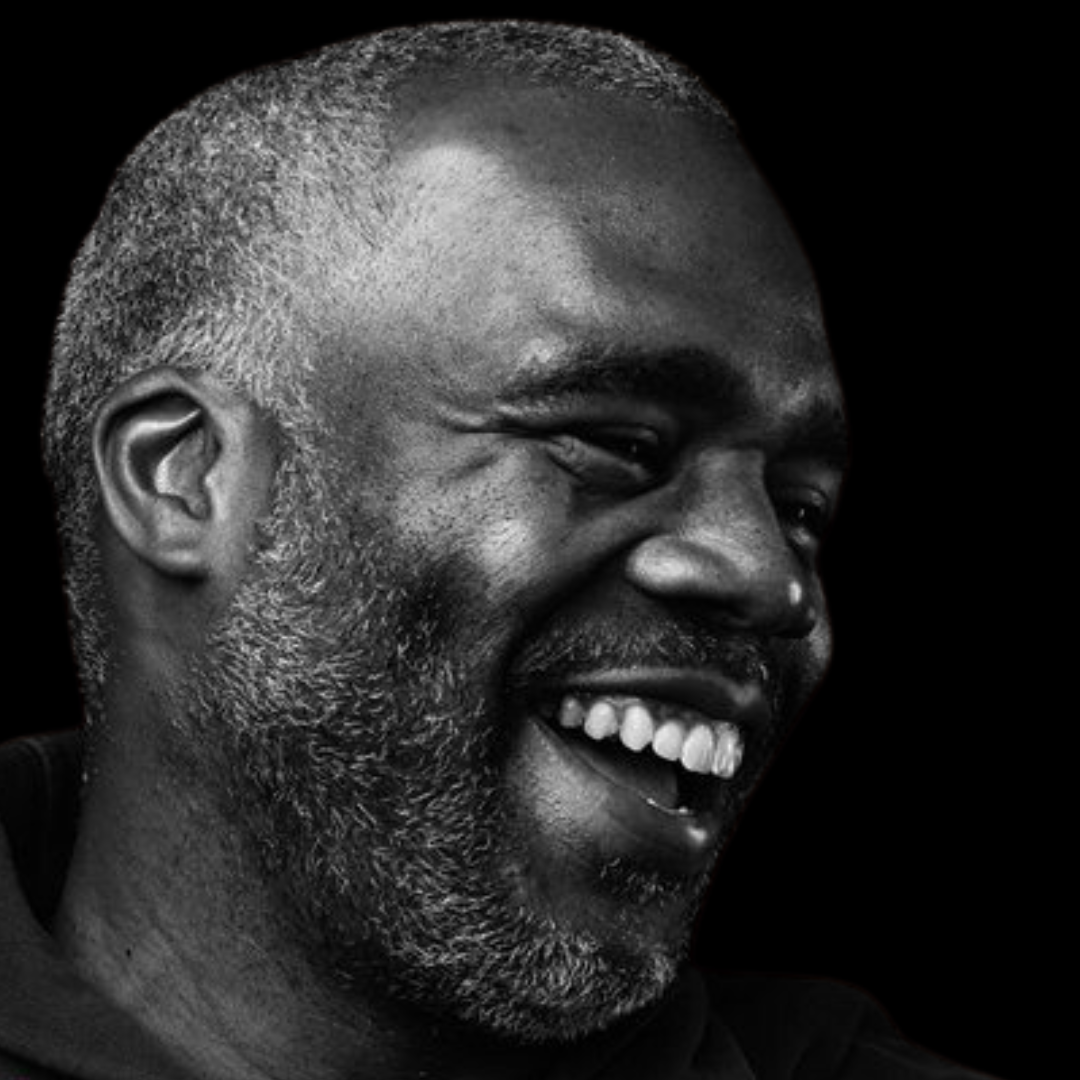

Shaping the Future of Environmental Justice: A Conversation with MSC’s Environmental Fellow

September 7, 2023

Movement Strategy Center Explores Architecture, Community Engagement, and Mentorship with Walter HuntAt the core of the environmental movement is a vision to reshape and align our communities toward a regenerative relationship with the earth. At Movement Strategy Center (MSC), we’re not just embracing this vision; we’re cultivating the leaders who…

Growing Hope: Cultivating a Resilient Future in

Sandbranch, Texas

August 3, 2023

Movement Strategy Center Shares the Sandbranch Revitalization Fund’s ProgressSandbranch’s relationship with water paints a poignant narrative of resilience. The absence of safe, clean water reverberates throughout the entire fabric of the community, touching upon every aspect of life — people, productivity, and the natural world alike. Yet, amid these…

In Memoriam:

ibrahim abdul-matin

July 12, 2023

Movement Strategy Center Remembers ibrahim abdul-matin, Environmental Activist, Urban Strategist, and Dear Friend of the MSC EcosystemIt is with heavy hearts that we mourn the loss of ibrahim abdul-matin, a bright, playful spirit who made a lasting impact as an environmental activist, urban strategist, and beloved friend. At 46, he leaves behind his devoted wife…

A Deeper Dive Into Felix Cove Flora

July 12, 2023

Movement Strategy Center Explores Point Reyes National Seashore with FSP Alliance For Felix CoveThis spring, the MSC communications team had the opportunity to tour Felix Cove, an enchanting corner of the Point Reyes National Seashore in northern California. The visit was led by Theresa Harlan, visionary founder and executive director of the Alliance for Felix…

Exploring Felix Cove: A Journey of Indigenous Heritage and Advocacy

June 21, 2023

Movement Strategy Center Explores Point Reyes National Seashore with FSP Alliance For Felix CoveIn the ever-growing movement to restore Indigenous lands to Indigenous hands, the Alliance for Felix Cove stands at the forefront in Northern California, fiercely fighting to protect, restore, and rematriate the ancestral homestead of the Coast Miwok/Támal-ko Felix…

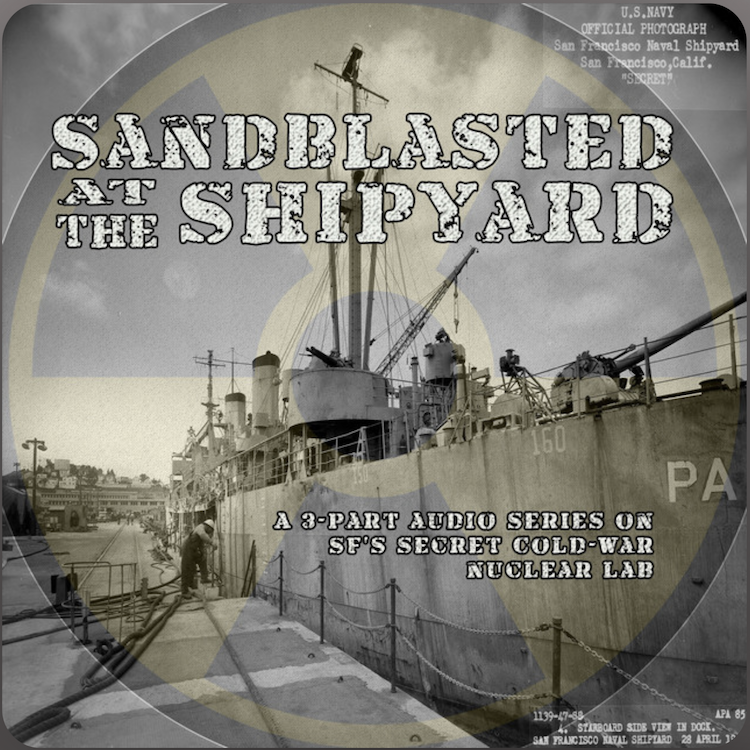

New Podcast on Hunters Point Naval Shipyard Features Advocates for Environmental Justice in San Francisco

June 14, 2023

MSC Chats with Breathe’s Tania Abdul, Journalist Rebecca Bowe, and Activist Renay Jenkins about the Series and Bayview-Hunters PointEarly this year, Breathe, a Bay Area fiscally sponsored project of MSC, partnered with freelance journalist Rebecca Bowe to release a three-part podcast called Sandblasted at the Shipyard. It covers the history of contamination at…

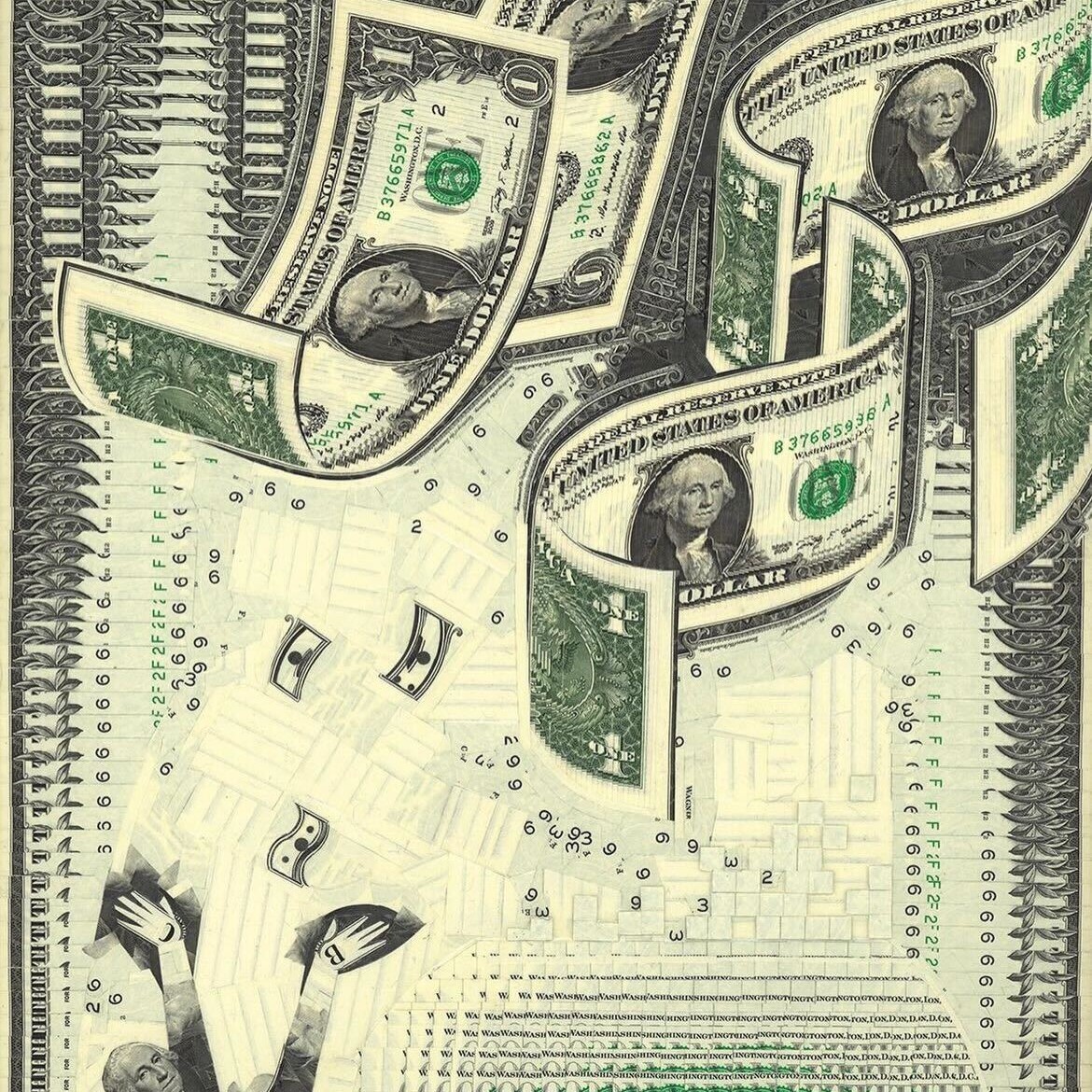

Moving Money Where it Matters

June 6, 2023

Movement Strategy Center on Shifting Philanthropic Power Dynamics Towards Interdependence and ResilienceEvery degree of warming intensifies the risk of species extinction, highlighting the urgency of addressing climate change. As we watch the weather report on any given day, the unfolding realities of our changing climate become strikingly evident — the record…