Movement Strategy Center Considers Water Equity, the Clean Water Act, and the Repercussions of Sackett v. EPA

Water seems fairly innocuous — you open your tap and water comes out. You assume it’s safe, it’s clean, it’s drinkable. Maybe you prefer Poland Spring or Lacroix, or you use a Brita, but you assume you can drink your water. You certainly feel comfortable bathing in it, washing your dishes with it, using it to prepare meals, or sloshing it into the dog bowl.

But water is a hot topic right now. Take the recent crises in Mississippi’s capital, the years of inaction and litigation in Flint, Michigan, and our country’s generally poor water infrastructure in many majority BIPOC cities and towns. At Movement Strategy Center (MSC), we are crowdfunding in support of the residents of Sandbranch — a Texas Freedman’s Settlement that still lacks clean, running water, despite its location just outside Dallas, one of the most prosperous cities in our country.

Our water is a hot topic at the Supreme Court, too. Sackett v. EPA is an upcoming U.S. Supreme Court case that could broadly affect the Clean Water Act, which was ratified way back in 1972 and just celebrated its 50th anniversary. And it may wind up being the most significant attack on America’s clean water laws since the 1970s.

If you’re unfamiliar with the Sackett case, it involves a couple who hoped to build a home near a lake in Idaho. To do so, they began to fill the property — a federally protected wetland — with gravel. The EPA, citing the Clean Water Act and its broad protection of the “waters of the United States,” halted the work and required the gravel’s removal. That was back in 2007. Since then, the case has bounced around the court system and will now be heard before the Supreme Court.

The Sacketts’ lawyers will argue that the wetlands in question are not “waters of the United States,” and thus not subject to federal regulation.

We know what you’re thinking. It’s water; and it’s in the United States. What’s the question?

We turned to the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) for a little clarity. Per Jon Devine, the director of NRDC’s federal water policy team: “Congress intended the phrase to be interpreted very broadly.”

When lawmakers were drafting the Clean Water Act … They envisioned its protections as extending to all the various bodies of water that make up a watershed, many of which people use for recreation, fishing, and drinking-water supply. And while those lawmakers may not have been hydrologists, they nevertheless understood the fundamental interrelatedness of these different bodies of water. “So the very earliest regulations set forth by the EPA were inclusive … All the relevant parts of an aquatic ecosystem, including streams, wetlands, and small ponds — things that aren’t necessarily connected to the tributary system on the surface, but that still bear all kinds of ecological relationships to that system and to one another.

He noted that, over the years, various parties — often developers and polluters — have attempted to litigate the meaning of the term; and until the early 2000s, those parties usually lost.

The Clean Water Act was nonpartisan, and it was passed in reaction to massive fish die-offs and dangerous levels of mercury and raw sewage in our waterways.

In 2006, another case surrounding another wetland drainage project was brought before the Supreme Court. Justice Anthony Kennedy stuck to the script — his opinion maintained that “waters of the United States” didn’t need to be visibly contiguous to warrant protection; and that if destroying or polluting one wetland or pond or creek could affect the health of a second body of water, then said waterway deserves protection. Both the Bush and Obama administrations subscribed to this viewpoint.

That said, conservative Justice Antonin Scalia saw things differently: his opinion centered on navigable waters. If it can’t accommodate a boat — well, protection shouldn’t be necessary.

That opinion, though ludicrous, was supported by the Trump administration and has opened the door to cases like Sackett v. EPA. And, crucially, it could make poking holes in the Clean Water Act a whole lot easier. And that’s a travesty: the Clean Water Act was nonpartisan, and it was passed in reaction to massive fish die-offs and dangerous levels of mercury and raw sewage in our waterways — not to mention the fact that Ohio’s Cuyahoga River literally caught fire and Lake Erie was projected to become biologically dead.

And while our waters have improved immensely, many waterways are still unhealthy and face further degradation from “forever chemicals” and increases in urban and agricultural run-off as developers pave over natural spaces and farmers and property owners doubledown on fertilizer and pesticide use. That’s to say nothing of climate change: drought, water scarcity, and just how hard our wetlands work in storing carbon.

We hope the Clean Water Act remains intact in the face of our overwhelmingly conservative Supreme Court. And, like Kennedy’s subscription to the interconnectedness of American waters — from seasonal ponds and small swaths of wetland to our largest lakes and most powerful rivers; we must recognize the interconnectedness and intersectionality of the American water system. We can not forget our brothers and sisters in Sandbranch, and in other communities all over the country that lack clean water infrastructure.

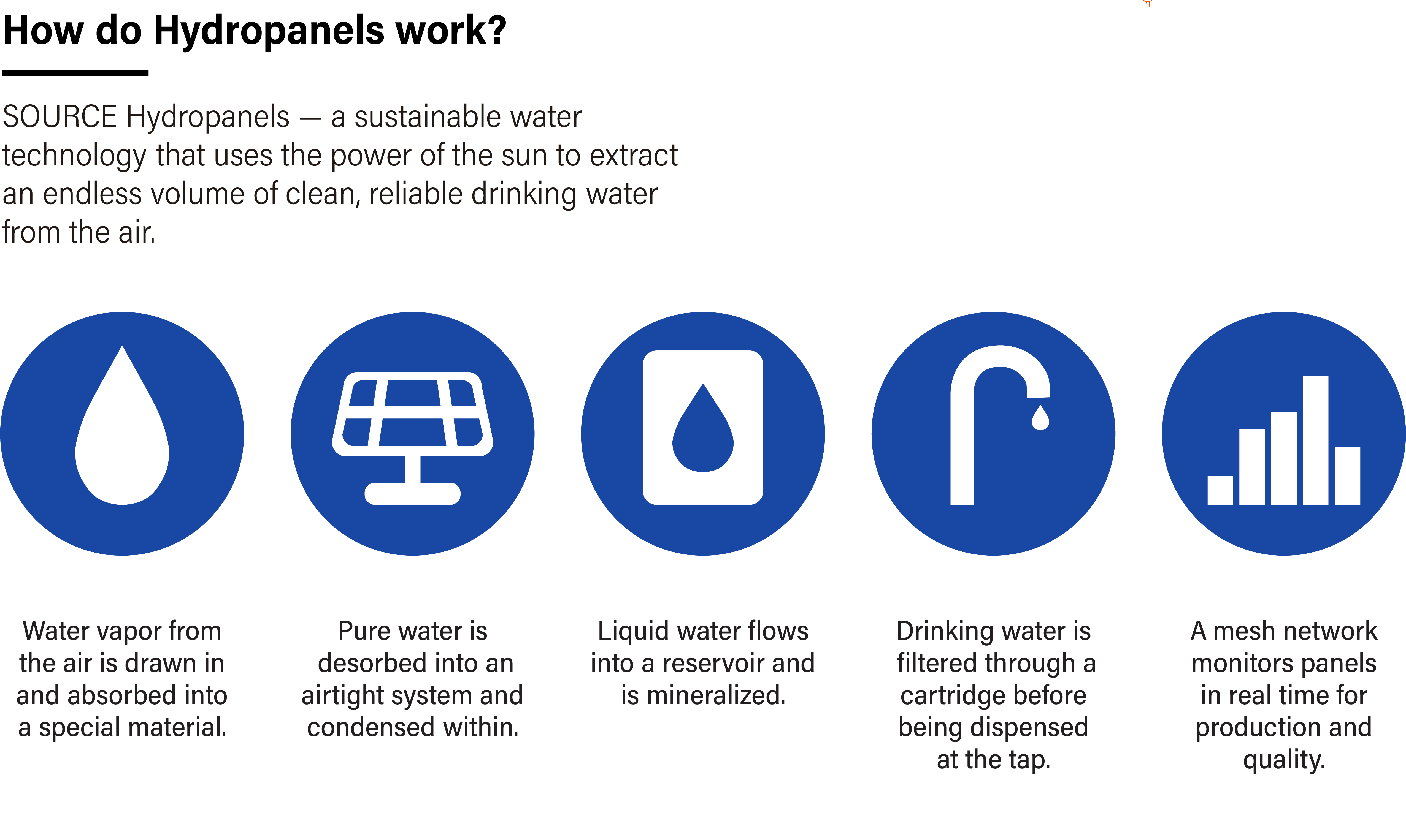

The people of Sandbranch — property owners and taxpayers — are represented by the Sandbranch Planning Committee and are working tirelessly to not only bring water to their community, but increase access to fresh food, equitable healthcare, and basic infrastructure (streetlights, trash removal, signage) to their community. With help from MSC, the Chisholm Legacy Project, and the Until Justice Corporation, the Sandbranch Revitalization Fund is starting with the installation of Hydropanels — a solar-powered system that can supply households with safe, clean running water pulled directly from the atmosphere.

The National Wildlife Federation (NWF) has joined the crusade. The organization is sponsoring Hydropanels for two homes in the community while working to raise additional funds and urge other large environmental organizations to make similar investments in Sandbranch and other frontline communities struggling to access clean drinking water.

“It is shameful that hundreds of years after its founding by emancipated men and women, this community does not have reliable access to clean and safe water,” said Dr. Adrienne Hollis, vice president of environmental justice, public health, and community revitalization at the NWF.

Members of NWF and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) joined Tonette Byrd, who leads the local Until Justice initiative and has led efforts to bring Hydropanels to Sandbranch, at a town hall meeting in October. Byrd, who has worked closely with the community and built relationships with its members, said in an interview, “this community deserves better and what I see happening in this community should not happen anywhere in the United States.”

She continued: “we are thrilled to be working with the community to ensure that this innovative technology can begin to help address these historic environmental injustices and provide renewable, reliable, and affordable water for community residents. Other environmental groups, federal, and state partners should invest in this and other similar efforts to address water insecurity in frontline communities in Texas and across the country.”

The members of this community have been oppressed by systemic racism and environmental injustice for over a century. Phyllis Gage, a longtime resident, said, “we’re paying taxes. So where’s my tax money going?” Her comments remind us that these Americans need far more than Hydropanels. These are a sort of band-aid — residents need city water and sewage services, food justice, land justice, and opportunity; and all of it must be rooted in a Just Transition.

“This innovative technology can begin to help address these historic environmental injustices and provide renewable, reliable, and affordable water for community residents.”

Food scarcity has become a central aspect of their plans: a centralized, community Hydropanel will maintain a community garden to grow fresh produce for Sandbranch residents. Meanwhile, residents point to their rising property taxes — in 2020 tax rates doubled and, in some cases, tripled for landowners. This despite the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) designation that limits property improvements and buyout offers beginning in 2005 that offered some residents only $350 for their properties.

Sandbranch’s water crisis touches every part of every resident’s life — how could it not? Safe, clean water is essential — to people, to productivity, to the natural world. It’s all connected — much like the “waters of the United States” cited in Sackett v. EPA. We need the Clean Water Act to remain intact. And, in Sandbranch, we need to support the installation of Hydropanels — a first step in bringing equity to this tiny but mighty Texas community. Please donate what you can to the #SandbranchIsRising campaign; and please share this blog. Water is life.